Mass Surveillance Is Legal in the EU. Here's What That Means for You.

Updated: November 2025

The European Union claims to be the world's privacy champion. The GDPR. Strong data protection laws. Court rulings that supposedly protect citizens from government overreach.

But here's the uncomfortable truth: mass surveillance is legal in the EU. Not just tolerated. Not just ignored. Explicitly legal under specific conditions, approved by both the European Court of Justice and the European Court of Human Rights as recently as 2024.

If you live in Europe and thought you were safe from the kind of bulk data collection that Snowden exposed in 2013, you need to read this.

What the Courts Actually Said

Between 2014 and 2024, European courts handed down dozens of rulings on mass surveillance. Privacy activists hoped these decisions would ban blanket data retention and bulk interception outright.

That didn't happen.

Instead, courts created a framework that permits mass surveillance under certain conditions. A joint factsheet released by the European Court of Human Rights and the EU Fundamental Rights Agency in February 2025 outlines the conditions under which bulk interception is considered compatible with EU and ECHR law.

The courts ruled that governments can:

- Retain all your communications data (who you contact, when, where, for how long)

- Intercept bulk internet traffic crossing borders

- Store encrypted messages and demand decryption keys from service providers

- Access your data without telling you

But only if they follow specific rules.

The "Safeguards" Are the Catch

Here's how the legal framework actually works.

Courts said mass surveillance is acceptable if:

1. It targets national security threats

Fighting "serious crime" isn't enough to justify bulk data collection. But national security? That can justify it, provided the government proves the necessity and implements proper safeguards. Terrorism. Threats to constitutional order. Espionage. All potentially valid reasons for mass surveillance, subject to a proportionality test and independent oversight.

The 2020 La Quadrature du Net ruling (CJEU C-511/18, C-512/18, C-520/18) made this distinction explicit. You cannot do general data retention to catch drug dealers. But you can do it to stop terrorists, if the threat is proven and safeguards are in place.

2. The threat must be "genuine and present or foreseeable"

This sounds strict. It isn't.

Governments don't need an active terrorist cell operating in their territory. They just need to argue that a threat is "foreseeable." In practice, that bar is low enough to drive a surveillance apparatus through.

3. There must be independent oversight

Not prior judicial authorization. Not warrants for specific individuals. Just "independent oversight" by a court or administrative body after the fact.

The 2021 Prokuratuur case (CJEU C-746/18) clarified that prosecutors cannot authorize data access because they lack independence from the investigative process. Police oversight units may qualify as independent authorities, but each Member State must demonstrate that these bodies have true operational independence.

4. Data retention must be "limited in time"

The CJEU has repeatedly struck down retention periods it considers disproportionate. The 2014 Digital Rights Ireland decision (C-293/12) invalidated the Data Retention Directive's requirement for storage between six months and two years, calling it excessive. Six months was later challenged in other cases. Fourteen months was found problematic in Slovenia. Seventy-two months (six years) remains in effect in Italy as of November 2025, despite courts calling it excessive in principle.

The problem? The courts never defined a specific time limit. There's no uniform EU standard. Each case is assessed individually for proportionality, leaving member states to guess what duration might survive judicial review.

5. Security measures must protect stored data

This means encryption, access controls, and procedures for destroying data eventually. It does not mean the data won't be collected in the first place.

6. You might get notified. Eventually. Maybe.

If notification "does not hamper criminal proceedings," you may be informed that your data was accessed. But there's no guarantee. And "hampering proceedings" is interpreted generously.

The UK, Poland, France, and Italy: Real-World Examples

These aren't theoretical concerns.

United Kingdom (Big Brother Watch v. UK, 2021)

The European Court of Human Rights found the UK's bulk interception regime violated Article 8 (privacy) and Article 10 (freedom of expression). The court specifically criticized the lack of independent authorization for surveillance warrants, insufficient safeguards for journalistic sources, and inadequate protections against arbitrary access to intercepted data.

Critically, the court did not ban bulk interception itself. It said the UK's system could be made compliant by reforming the safeguards.

The UK has since updated its laws under the Investigatory Powers Act. Bulk interception continues. Note that the UK left the EU in 2020, so its surveillance regime is now governed by domestic law, though it remains subject to European Court of Human Rights oversight.

Poland (Pietrzak and Bychawska-Siniarska v. Poland, May 2024)

Polish law gave police and intelligence services permanent, direct, and unlimited access to communications data without needing to ask telecom providers. The ECtHR found this violated Article 8, specifically condemning the blanket nature of retention, the absence of independent oversight, and the indefinite duration of the regime.

The court called for legislative reform to bring the system into compliance with Convention standards. It stopped short of ordering Poland to dismantle data retention entirely. Instead, it urged the government to implement proper safeguards and independent authorization mechanisms.

Poland's surveillance system is still operational pending these reforms.

France (Conseil d'État, April 2021)

France's highest administrative court ruled that generalized data retention for national security purposes was compatible with EU law. The Conseil d'État interpreted the CJEU's Tele2 Sverige precedent narrowly, giving the French state a broad margin of appreciation to maintain its bulk retention regime. French authorities can retain all communications data, provided they periodically review whether a serious security threat still exists.

This decision was controversial and criticized by privacy advocates for giving excessive deference to national security claims. Despite the criticism, France kept its bulk retention regime.

Italy (still unresolved in November 2025)

Italy retains all communications metadata for 72 months under Law No. 167/2017. That's six years. This applies to traffic and location data (who you contact, when, where), not the content of communications. But there's no distinction between national security and ordinary crime investigations. No targeted retention. Just blanket collection of everyone's metadata.

The Tribunale di Rieti referred this regime to the CJEU in May 2021, but withdrew the case after Italy made minor changes to access procedures in November 2021. Those changes introduced judicial authorization requirements but left the six-year retention period for metadata in place.

What This Means for You

If you use a phone or the internet in the EU, your data is likely being collected and stored right now. Not because you're suspected of a crime. Not because you're under investigation. But because governments decided it's useful to have everyone's data on hand just in case.

Your telecom provider is required by law to keep:

- Every phone number you call or text

- Every website you visit

- Your location data every time you connect to a cell tower

- Your email metadata (who you email, when, how often)

- Your IP address and login times

This isn't targeted surveillance. It's everyone, all the time, by default.

The GDPR doesn't protect you from this. The GDPR explicitly allows member states to restrict data protection rights for national security purposes under Article 23, which permits derogations "to safeguard national security, defence, public security, and the prevention, investigation, detection or prosecution of criminal offences." The courts confirmed this exception is valid.

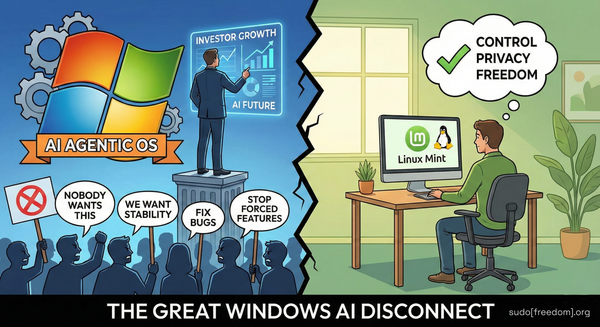

Why Civil Society Pushed for a Total Ban

After the 2013 Snowden revelations, privacy organizations like Digital Rights Ireland, Privacy International, and La Quadrature du Net argued that mass surveillance should be prohibited entirely. Not regulated. Not safeguarded. Banned.

They pointed out that:

- Mass surveillance treats everyone as a suspect

- It violates the presumption of innocence

- It has a chilling effect on free speech and journalism

- Safeguards don't prevent abuse once the data exists

The African Declaration on Internet Rights and Freedoms, for example, states plainly: "Mass or indiscriminate surveillance constitutes a disproportionate interference, and thus a violation, of the right to privacy."

But European courts took a different path. Instead of banning mass surveillance, they tried to regulate it. The result is what scholars call the "constitutionalization of mass surveillance." Not its elimination. Its integration into the legal framework.

The Legislatures Are Lagging Behind

Here's the frustrating part.

Courts have now spent more than a decade issuing rulings on what mass surveillance systems must include to be lawful. Independent oversight. Judicial review. Time limits. Protections for journalists.

Most EU governments have ignored this guidance.

Belgium finally reformed its system in 2022 after repeated court defeats. Germany is still debating what to do. Italy made cosmetic changes and kept its six-year retention period. France doubled down.

The European Commission proposed a new e-Privacy Regulation to replace the outdated 2002 Directive. That proposal was stuck in negotiations for years. One of the sticking points was whether to exclude national security surveillance from EU law entirely, letting member states do whatever they want.

In February 2025, the Commission formally withdrew the proposal, citing "no foreseeable agreement" and deeming it outdated. The original e-Privacy Directive (2002/58/EC) remains in force, leading to a fragmented patchwork of national regimes across the EU.

What You Can Do About It

You can't opt out of your government's data retention regime. It's mandatory for all telecom providers in most EU countries. But you can make it harder for that data to be useful.

1. Use end-to-end encryption for everything

Signal for messaging. Proton Mail for email. A VPN for internet traffic. Encrypt your communications so that even if metadata is collected, the content is unreadable.

But understand encryption's limits: End-to-end encryption protects the content of your communications. It does not hide metadata. Your telecom provider and ISP can still see who you're contacting, when, how often, and your approximate location. They log your IP addresses, connection timestamps, and traffic patterns. Even Signal, despite its strong encryption, cannot prevent telecoms from collecting metadata about when you connected to Signal's servers.

VPNs and Tor hide your destination from your ISP, but your ISP still knows you're using a VPN or Tor, and they log those connections. Metadata collection happens at the network level, before encryption even applies.

2. Avoid SMS and regular phone calls when possible

These are the easiest to monitor. Use encrypted voice and video apps instead (Signal, Wire, Element).

3. Use Tor or a trusted VPN

This won't stop your telecom provider from logging that you connected to a VPN. But it prevents them from seeing which websites you visit or what you do online.

4. Self-host when you can

If you run your own email server, file storage, or communication tools, you're not subject to the mandatory retention requirements that apply to commercial telecom providers. It's more work. But it removes you from the bulk surveillance pipeline.

Important caveat: Self-hosting does not automatically exempt you from national data retention obligations if your service is classified as a "public communications service provider" under national law. In practice, this classification usually applies to commercial providers serving the public, not individuals running personal servers. But the legal definition varies by country, and running a service that others use could potentially trigger reporting requirements.

sudo[freedom].org has step-by-step guides on all of this.

5. Support organizations fighting this in court

Groups like Privacy International, La Quadrature du Net, and European Digital Rights (EDRi) are still pushing for stronger protections. They need funding and public pressure to keep going.

The Bottom Line

Mass surveillance in the EU isn't a dystopian future. It's current law. It was litigated, challenged, and ruled on by the highest courts in Europe. And those courts said it's legal, with conditions.

The conditions aren't enough.

The ECtHR and FRA's February 2025 factsheet outlines the conditions under which governments can engage in "bulk interception" and "general retention" of communications data as long as they follow procedural rules.

But once the data exists, it's vulnerable. To hackers. To rogue employees. To mission creep. To political abuse. Safeguards can be weakened. Oversight can be defunded. Time limits can be extended.

The only real protection is not collecting the data in the first place.

European courts refused to go that far. So it's up to individuals to protect themselves.

Encrypt your life. Self-host when possible. Use tools that respect your privacy by design. And don't trust that the law will protect you, because the law now explicitly allows what Snowden warned us about.

![sudo[freedom].org](https://sudofreedom.org/content/images/2025/08/sudo.png)

![sudo[freedom]](/content/images/size/w160/2025/08/square.svg)